-

What is The Way of Python?

This blog is a collection of my thoughts on the philosophy of Python and how it can be applied to improve various aspects of software development, including engineering, architecture, design, and the happiness and satisfaction of developers. I hope it will help making enlighten choices that will make your team more happy and efficient.

Recent articles of the blog:

- Exploring Dict and HashMap in Python and Rust

- External VS Internal solution: Reliability

- FOR vs WHILE: How to choose?

- Do you enumerate?

- Make simple things simpler?

Content of the blog

In an nutshell: The Python philosophy

The philosophy of Python is captured in PEP 20 – The Zen of Python, which is a collection of guiding principles for writing computer programs that influence the design of the Python language.

The Zen of Python can be accessed by running the following command in a Python interpreter:

import this

The Zen of Python includes principles such as “beautiful is better than ugly”, “explicit is better than implicit”, and “simple is better than complex”. These principles emphasize the importance of readability, simplicity, and minimalism in Python code. The philosophy of Python encourages programmers to write code that is easy to understand, maintain, and improve upon. Of course, this philosophy can also be applied to software design and architecture.

In addition to the Zen of Python, there are other concepts that are important in the Python and software engineering community, such as the idea of Pythonic code, the clean code and SOLID principles, etc. Zen of Python is just the tip of the iceberg, we will delve deeper in the Python philosophy.

In a nutshell: Software Engineering

“Software Engineering” refers to all aspects of professional software development, including technical issues such as development and extension, as well as human factors such as developer productivity, well-being, retention, and positive company culture. These topics are all interrelated and contribute to the overall success of a software development project.

I believe that both technical and human factors are equally important for a company’s success. Companies want employees who will stay with them for a long time to minimize the cost and disruption of frequent hiring, and to retain valuable knowledge and skills. At the same time, companies want to be able to adapt, change, and improve their software in an efficient and cost-effective manner. By prioritizing these factors in our work, we can create the most valuable and profitable products for companies, and increase our own chances of being well-compensated for our contributions while achieving personal happiness and satisfaction.

How Python helps for software engineering?

The Python philosophy emphasizes simplicity, readability, and explicitness, which can be applied to software engineering to create code that is easy to understand, maintain, and extend.

Through my experience teaching, coaching, training, and working with hundreds of people on Python and software development, I have observed that certain behaviors can lead to increased happiness and efficiency among developers, while others can cause difficulty and unhappiness. I want to address this issue and contribute to the success and happiness of all software engineers, as I strive to do in my own work.

And the first advice among many is:

You should care about what you do.

When you care about your work, you are more likely to be motivated and produce high-quality results, as well as find personal fulfillment and satisfaction in your contributions.

And more…

From general knowledge of Python and other tools

Some article will delve deeper into the topic of Python, including its features, libraries, and lesser-known gems within the language.

For example:

- Python call-by-assignment, in opposition to the call-by-value or call-by-reference,

- 2 closure layered decorators,

- Context management,

And many more…

To myth busting and other misconception around the Python language

There is a lot misconceptions around Python, from believes that turns out to be wrong to absolute myth.

For example:

- Python is a weak typed language (not, it’s not!)

- __init__() method is not a constructor (yes, it is!)

- % string formatting is dead (no, and logger will thank you!)

And many more !

You need to start somewhere

Check out most recent articles:

- Exploring Dict and HashMap in Python and Rust

- External VS Internal solution: Reliability

- FOR vs WHILE: How to choose?

- Do you enumerate?

- Make simple things simpler?

Or this selection:

-

Exploring Dict and HashMap in Python and Rust

Learn Python with Rust: Counting String Occurrences

Let’s learn Python by looking at another language, Rust. Here is a Python pedagogical simplistic example that counts string occurrences in a list (could be done using

Counter, I know), and the Rust counterpart (I know, could be done usinginto_iterandfold).# Python def foo(spam: list[str]) -> dict[str, int]: counter = {} for item in spam: counter[item] = counter.setdefault(item, 0) + 1 return counter// Rust fn foo(spam: Vec<String>) -> HashMap<String, i32> { let mut counter: HashMap<String, i32> = HashMap::new(); for item in spam { *counter .entry(item) .or_insert(0) += 1; } counter }Data Structures: Dict and HashMap

First, we define a

dictin Python or aHashMapin Rust. Pythondictcan take any type of value by default, but both structures are hashmaps, meaning they bind a hash to a value. The value can be of any kind, but the key must be hashable (implement a__hash__magic method). Immutable types are usually hashable, but not always. For example, a tuple containing a list cannot be hashed (here is why).In Rust, the

HashMapmust be declared asmut, meaning mutable. Pythondictare mutable by default. To create an immutable dict, you can use a mapping proxy (or the tier library frozendict):import types immutable_dict = types.MappingProxyType({'a': 1, 'b': 2})Code Comparison

Rust Code

counter.entry(item).or_insert(0)accesses the entry associated with the keyitem, and if it’s vacant inserts0into the entry and returns it. This is the important part: It change the value of the entry and return this entry at the same time.In order to update the value, we use the wildcard

*and+= 1. This will access and mutate the entry, adding 1 to the current count.Python Code

The Python equivalent,

counter.setdefault(item, 0), returns the value associated to the key if it exists, and If the key doesn’t exist in the dict (meaning there is no value), it set it to the default value, here0and returns it.However, the result is a simple integer, not a reference to the dict value. Therefore, we need to increment the value explicitly with

counter[item] = counter.get(item, 0) + 1.Mutable vs Immutable Data Structures

In Rust, the or_insert call on a HashMap entry, give us a mutable reference to the entry inside the HashMap. Therefore the mutable state allow us to += its value, directly altering the HashMap. To do that we need

*to dereference the mutable and get access to it. In Python,.setdefaultreturns a value, not a reference, so we must write it back to the dict withcounter[item] =.Hypothetical Python Enhanced Syntax

To achieve something similar to Rust in Python, we might want syntax like using a walrus operator:

(counter[item] := counter.get(item, 0)) += 1

Unfortunately, this isn’t valid Python syntax, although It is possible by altering the bytecode of a similar function (see codereview.stackexchange.com).

Enhanced versions

More pythonic code

To be clear, the python code showed previously in this article is not what you should aim for as It lack simplicity and conciseness. Here is a few improvement you might want to consider if you are looking for a more pythonic code.

Use collections.defaultdict instead of dict

The

collections.defaultdictobject allows you to define a default factory of value for each missing key that could be asked from the dict. By defining this default factory to int, the dict will generate a new int each time the key is missing. Then, the key is returned, effectively doing in valid Python what the hypothetical implementation using the walrus would do. Of course, it doesn’t looks like the Rust version at all anymore.import collections def foo(spam: list[str]) -> dict[str, int]: counter = collections.defaultdict(int) for item in spam: counter[item] += 1 return counterUse collections.Counter when you count something

What if we use something called Counter

in the collectionsmodule? It should count stuff, right? Let’s change the counter definition first.import collections def foo(spam: list[str]) -> dict[str, int]: counter = collections.Counter() for item in spam: counter[item] += 1 return counterAnd it works. But that wouldn’t be very useful, isn’t it? I mean, we still have to perform a for loop and increment our-self. A object named “Counter” should be able to count stuff without our help, right? Well, it does.

def foo(spam: list[str]) -> dict[str, int]: return collections.Counter(spam)Yes, now the function is pretty much a useless and confusing abstraction over Counter, but you get the point. Count stuff in python, think about

collections.Counter!More rustonic code

Same as the python code, there is better implementation to perform that task in rust, slightly more complex to do in Python, that’s why I didn’t used it in this article, but we’ll see those implementation now.

Use of Entry.and_modify() when modifying something

You cannot get a reference to an Entry that could be vacant as the compiler will not compile, simply because without making sure an entry is Occupied, there is no guaranty that the reference of the value could be acquired (the

Occupied.get()method allows you to get a ref to the value). So, you need to perform aEntry.or_insert()before the+=.But, you want to perform the

+=only when there is already a value to increment, right? Let’s change our code to useEntry.and_modify()then.fn foo(spam: Vec<String>) -> HashMap<String, i32> { let mut counter: HashMap<String, i32> = HashMap::new(); for item in spam { counter .entry(item) .and_modify(|counter| *counter += 1) .or_insert(1); } counter }Doing so, the increment will only be performed when the value already exists in the HashMap, and if it doesn’t, the inserted value is set to 1, since we don’t perform the increment after the insertion.

No more loop, let’s go functional

If you are used to

functools.reduce()in Python, the following won’t be difficult to understand. If you are not, I advise you to look into it before.So, what do we do with our code? We want to do something for each value of the list of strings. Each time we perform this “something”, we take the result and give it back to the next operation. Sound pretty familiar, right? Let’s write it in Python first.

def foo(spam: list[str]) -> dict[str, int]: return functools.reduce( lambda counter, s: counter | {s: counter.get(s, 0) + 1}, spam, {}, )The Rust functional implementation is slightly different, let’s see how it would hypothetically looks like in Python.

def foo(spam: list[str]) -> dict[str, int]: return spam.reduce( lambda counter, s: counter | {s: counter.get(s, 0) + 1}, {}, )Of course, this will crash because

str.reducedoesn’t exists, but it could make sense, right?This

str.reducesignature would looks like this:def reduce(self: Iterable[_S], function: (_T, _S) -> _T, initial: _T) -> _TLet’s alter it a little bit more (still won’t be functional code).

def foo(spam: list[str]) -> dict[str, int]: return iter(spam).fold( {}, lambda counter, s: counter | {s: counter.get(s, 0) + 1}, )Now, we first convert the string is a more generic object, an iterator, that could hypothetically have a function named “fold” that would simply be an alternative reduce where the initial value is the first parameter instead of the last one.

The signature of this hypothetical

Iterator.foldfunction would looks like this:def fold(self: Iterator[_S], initial: _T, function: (_T, _S) -> _T) -> _TYou start to see where I’m going? Let’s look at the Rust implementation.

fn foo(spam: Vec<String>) -> HashMap<String, i32> { spam .into_iter() .fold( HashMap::new(), |mut counter, item| { counter .entry(item) .and_modify(|counter| *counter += 1) .or_insert(1); counter }, ) }Yes, this behave exactly like our fictional python code. Easy, right? Maybe not. Let’s see.

spam.into_iter()is roughly equivalent toiter(spam)- .fold() is equivalent to the fictitious fold method we talked before.

|mut counter, item| {...}is called a closure and this is roughly equivalent to our lambdas.

This article was reviewed and improved by following reviewers, thank you

Antony Bara, Maxim Danilov. -

External VS Internal solution: Reliability

External solutions often undergo rigorous testing and widespread use, making them more reliable. Internally developed solutions may lack the same level of scrutiny and real-world validation. Reliability is a cornerstone of effective software development. When considering the adoption of external solutions versus developing internal ones, the reliability factor often tips the scale in favor of established external tools.

Reliability: The Case for External Solutions

The reliability of external solutions often surpasses that of internally developed alternatives due to extensive production testing, ongoing iteration and improvement, and robust community support. While pride and the desire for custom solutions can drive NIH syndrome, the practical benefits of adopting proven external tools—especially their reliability—cannot be overlooked. By leveraging these external solutions, organizations can avoid the pitfalls of technical debt and inefficiency, focusing instead on innovation and value addition.

Extensive Production Testing

External solutions have typically been in use for a longer period, undergoing extensive testing in a variety of production environments.

Stress-Tested

External solutions are often used by a wide user base, ranging from small startups to large enterprises. This diverse usage ensures that the software is stress-tested under different scenarios and workloads, revealing potential weaknesses that might not surface in a limited internal testing environment.

Validated by Experience

The experiences of thousands or even millions of users help in identifying and resolving edge cases and obscure bugs. This level of real-world validation is hard to replicate with an internally developed solution, which might only be used by a limited number of users within the company.

User Feedback Loop

With a large user base, external solutions benefit from continuous feedback. Users report bugs, suggest features, and share performance insights, creating a feedback loop that drives continuous improvement. This iterative process ensures the software becomes more reliable over time and is highly valuable for users of such solutions.

Iteration and Improvement

Established external solutions benefit from multiple iterations and a continuous improvement process. Companies love Agile methodologies, sprints, and other rituals. If we take a closer look at external solutions, they often have already undergone hundreds of thousands of iterations, making it hard for internal projects to compete.

Regular Updates

Developers of popular external tools regularly release updates that include bug fixes, performance enhancements, and new features. These updates are often driven by user feedback and emerging industry standards, ensuring the software remains robust and relevant.

For example, the data validation library “Pydantic” releases updates every few weeks to every month (pydantic/releases).

Performance and Memory Optimizations

Through ongoing optimization efforts, external solutions become more efficient. Performance bottlenecks are identified and addressed, and memory usage is optimized, resulting in a more stable and efficient product. Achieving similar levels of optimization with an internal solution would require significant time and resources.

Community and Ecosystem Support

The broader community around external solutions contributes significantly to their reliability.

Community Contributions

Open-source and popular proprietary solutions often have active communities that contribute code, identify issues, and provide patches. This collective effort leads to a more resilient and feature-rich product.

To visualize the evolution of a codebase over time and the contributions made by the community, tools like Hercules can be very valuable. Hercules analyzes the repository history and can generates detailed graphs showing the survival of code lines. These visualizations help developers and project managers understand how community contributions have influenced the codebase over time.

SQLAlchemy line burndown. Generated with `hercules –burndown –first-parent –pb https://github.com/sqlalchemy/sqlalchemy | labours -f pb –resample year -m burndown-project` Comprehensive Documentation

External solutions usually come with extensive documentation, created and refined over time. This documentation helps users understand the intricacies of the tool, troubleshoot issues, and implement best practices, enhancing the overall reliability of the solution.

Internal Development Challenges

In contrast, internally developed solutions face several challenges that can compromise reliability.

Limited Testing

Internal solutions are typically tested by a smaller group of users in a controlled environment. This limited scope can fail to uncover bugs and performance issues that would become apparent under wider usage.

Resource Constraints

Developing a reliable, high-performance solution internally requires significant resources, including time, skilled personnel, and financial investment. Often, these resources are constrained, leading to compromises in the quality and reliability of the software.

Lack of Continuous Improvement

Unlike external solutions, which are continuously improved based on widespread feedback, internal solutions might not receive the same level of iterative enhancement. This can result in stagnation and technical debt over time.

Nuances

While the case for external solutions hinges on their reliability, it’s important to recognize that not all external libraries, packages, or frameworks are equal. The decision to adopt external tools must consider the specific nuances and individual characteristics of each option.

Extensive Production Testing

Not every external solution undergoes the same level of production testing. Some might be relatively new or niche, lacking the extensive stress-testing seen with more established options. It’s essential to evaluate the maturity and user base of an external tool to gauge its reliability accurately. Due diligence involves assessing how well the solution has been tested in environments similar to your own.

Iteration and Improvement

The frequency and quality of updates can vary significantly between external solutions. While some tools, like the data validation library “Pydantic,” release updates frequently to address bugs and enhance performance, others may have slower development cycles. Understanding the development lifecycle and commitment to improvement from the maintainers of an external tool is crucial in determining its long-term reliability.

Community and Ecosystem Support

The strength of community support can differ widely. Highly popular tools may have robust community contributions and extensive documentation, while less-known solutions might lack these benefits. When evaluating external solutions, consider the size and activity level of the community, as well as the quality and availability of documentation. This will help ensure that the tool you choose is supported by a vibrant ecosystem that can assist with troubleshooting and development.

Also, not everyone works the same way. When we examine the code ownership of Numpy, we observe something that might seem very strange: Eric Wieser became the owner of approximately 40% of the codebase in just one month, which is roughly equivalent to 250,000 lines of code.

How did he achieve this? By updating and reorganizing LAPACK in the Numpy codebase with these three pull requests:

- MAINT: Rebuild lapack lite

- Upgrade to Lapack lite 3.2.2

- MAINT: Split lapack_lite more logically across files

Due to these updates, the graph representing the Numpy code ownership is not entirely accurate but can still provide valuable insights, such as the proportion of code that is “generated” in Numpy (at least ~40%). Knowing this, the trust should not be attributed to Eric Wieser but rather to

f2c, a program that translates Fortran into C.Internal Development Challenges

Although internal development often faces limited testing, resource constraints, and a slower pace of continuous improvement, there can be exceptions. For instance, a company with dedicated resources and expertise might successfully develop a reliable internal solution tailored precisely to its needs. However, this is usually the exception rather than the rule, and internal projects must be critically assessed for their potential to overcome these common challenges.

-

FOR vs WHILE: How to choose?

When I began studying computer programming in C in my software engineering school, the use of for loops was forbidden. Using them would lead to receiving a grade of -42. The reason? To teach me the underlying logic of for loops with while loops. Now that I have the freedom to choose, when do I use for loops?

FOR vs WHILE: How to choose?

If you have the option to choose, this implies that it should be possible to use a for loop in situations where a while loop is used and a while loop in scenarios where a for loop was used. Let’s examine some examples.

Replace while loops with for loops

Let’s take a simple and usual while loop as an example:

import random a = random.randint(0, 100) while a < 10: print(a) a = random.randint(0, 100)This while loop can be replaced with an infinite for loop if you put a break inside the body of the for:

import itertools import random for _ in itertools.count(): a = random.randrange(100) if a > 50: break print(a)What is

itertools.count()? An infinite generator that will allows the loop to iterate for an unlimited amount of time. The for loop stops only because we “break” when the condition is met.Replace for loops with while loops

You will take a typical for loop in python:

text = "Hello World" for letter in text: print(letter)You can replace the for loop with a while loop by creating an index and increasing it until you reach the length of the text.

text = "Hello World" i = 0 while i < len(text): print(text[i]) i += 1Now you know how to change your while and for loops into the other kind.

The Rule of thumb

If you need to remember a rule that will help you most of the time, it’s this one:

Use For loops for known iteration number.

Use While loops for unknown iteration number.

Even if you can use both in almost any situation (I don’t have one where you can’t), this doesn’t mean that you should. Choose wisely. But be careful. Sometimes, we can “know” how many iteration would be required, but the code to actually determine that can be hard to read or understand. Don’t follow this rule if it lower readability and understanding of your code.

-

Do you enumerate?

Simple is better than complex. Zen of Python. You know that, right?

Well, we all do, but it’s less consensual when it comes toenumerate().“What is

enumerate()?” In a nutshell, it’s a function that returns something similar to a list of index-value pairs*. It is mostly used in for loops to iterate over a list to get all values and its associated index. But what if you only need indexes?*Enumerate returns an iterator. From the Python glossary: “[An Iterator is] an object representing a stream of data.”

I need indexes only

I’m new to Python, let’s do it

Most of the time, when developers discovers Python, they solve this issue with the combination of two functions:

range()andlen():for i in range(len(population)): print(i)Great, but many Pythoneers will then complains about your code as being “non-pythonic”.

“What the fuck is non-pythonic? or pythonic?”

[Pythonic means] exploiting the features of the Python language to produce code that is clear, concise and maintainable.

James, StackOverflow answer to What does Pythonic means?So, this means that you didn’t use the “Python” language “correctly”. Great, we have room for improvement (Yes, it’s a good thing!).

A pythonic approach

So, what is the pythonic approach to solve this issue (a big one, I know 😉)?

Well, let’s go back to the

enumerate()function and see how it can handle your problem:for index_value_pair in enumerate(population): print(index_value_pair[0])But it’s ugly

“Ok, but I though that the goal of “Pythonic” code was to be clear, concise and maintainable, this isn’t at all!”

No, it’s not. Because there is many things to consider when you want to produce a clear and meaningful code. First, a pair of value (as a list or a tuple) can be “unpacked” by Python into two variables. How does it works?

Yes, but less with unpacking

Let’s see an example of unpacking:

>>> spam, eggs = ["ham", "bacon"] >>> spam ham >>> eggs bacon

As explained in the Official Python Tutorial about Tuples and Sequences:

“The statement

t = 12345, 54321, 'hello!'is an example of tuple packing: the values12345,54321and'hello!'are packed together in a tuple. The reverse operation is also possible:>>> x, y, z = t

This is called, appropriately enough, sequence unpacking and works for any sequence on the right-hand side. Sequence unpacking requires that there are as many variables on the left side of the equals sign as there are elements in the sequence. Note that multiple assignment is really just a combination of tuple packing and sequence unpacking.”

So, how to be more pythonic with our

enumerate()? Use unpacking in the for loop of course (yes, it’s possible!):for index, value in enumerate(population): print(index)“Wow, it’s great!” Yes, but not enough.

Great but not enough for Pythoneers

Yes, that’s a huge improvement compared to accessing the first element of the pair to get the index. But it’s not enough if you follow the pythonic philosophy. Why? Because you don’t use the

valuevariable, and nothing is explicit about that.“But, how can I say that I don’t use something that I’m forced to use, because if I don’t, Python give me a pair of value?”

By using a Python convention: an underscore (“

_“) instead of a proper variable name to indicate that the variable is a placeholder to something you won’t use. Rembember Zen of Python “Explicit is better than implicit”.Let see how it looks like now:

for index, _ in enumerate(population): print(index)“Now, it’s perfect, except that… We use something that give more stuff than needed, when

range()andlen()give exactly what we need. Zen of Python didn’t also stated that Simple is better than complex?”Is enumerate() Pythonic for index only?

Disclaimer: Here is my opinion, and some may disagree. But let’s discuss pros and cons.

One call vs two

Simple is better than complex, and one function call instead of two is de facto easier to read and interpret.

1forenumerate(),0forrange(len())Garbage vs Perfect fit

The

enumerate()function do return useless values whererange(len())provide an iterator over all indexes only. Ok, one point forrange(len()).1forenumerate(),1forrange(len())Beginner friendly

Yes, you need to read documentation to understand how enumerate works. Yes, many tutorials, schools, and training courses only present the range(len()) way of getting indexes. Yes, unpacking is not as well known as we would want. Fair point,

range(len())do win this round too.1forenumerate(),2forrange(len())Efficiency

Nope, I won’t address this point here. Why? Because premature optimization is the root of all evil! Maybe in a future article. No point change.

1forenumerate(),2forrange(len())Does it works for everything?

This is the most complex part: is the solution able to handle every object that a for loop can handle?

Sequences and iterables

First, let’s see what kind of object for loop do accepts, by looking into the official documentation: The for statement is used to iterate over the elements of a sequence (such as a string, tuple or list) or other iterable object.

So for loops iterate over

sequencesanditerableobjects. What is aniterableobject? Again, official documentation: An object capable of returning its members one at a time.“But, this is amazingly broad!” Yes, it is. Let me give you a great example:

Lists are sequences. Lists can’t be infinite, because our computers have a limited amount of memory, and can’t store an infinite amount of data at the same time.

But

iterablesaren’t meant to store any data, just being able to give its values, one at a time. So we can have infinite iterable, such asitertools.count(),itertools.cycle()anditertools.repeat(). You can even create custom infiniteiterablesyourself, we will see that in a future article.Infinite length

“But… Infinite

iterablecannot have a length, do they?”No, they don’t. So

range(len())will crash. And unfortunately,iterablesdoesn’t needs to be infinite to crash when we uselen()on them, as the underlying magic method*__len__is not part of theiterableAPI**.*https://docs.python.org/3/glossary.html#term-magic-method

**called theiterableprotocol, consisting of the magic method__iter__and__next__, documentation about protocols for each type here.So, back to our topic, enumerate can:

- be used on both

sequencesanditerables, - be used on every object that could have been used in a for loop,

When

range(len())don’t and will crash if you got aiterableinstead.For me, this cost 10 points to

range(len()), for a final score of1forenumerate(),-8forrange(len())Conclusion

I strongly believe that

enumerate()should be used instead ofrange(len())when you want to get only indexes, even after considering all of its downsides.for index, _ in enumerate(population): print(index)You can continue your reading on those other articles:

- be used on both

-

Make simple things simpler?

I often encounter juniors during training sessions or when I join a new team.

They all have in common a simple, naive way to code. Is that bad in itself? I don’t think so. I prefer the simplicity and efficiency of FastAPI over the convoluted 100% DRY design of DjangoRestFramework. I prefer the naive and efficiency of Python over the complexity of C++, the boilerplate OOP required code of Java or the strange and destabilizing syntax of Lisp.

For seasoned python developers, are you confident when you start a pull-request review and noticed a

MetaSomething(type)and aSomething(meta=MetaSomething)? I’m not.So, there is something great with beginners code. Simplicity. But it’s fake simplicity, and there is something better than that: True simplicity.

Fake simplicity

A beginner’s code is simple mostly because it describe everything it does at a very low/granular level. Let’s see an example:

def count_living_per_year(population: list[tuple[int, int]]) -> dict[int, int]: living_per_year = {} for birth, death in population: for year in range(birth, death): if year in living_per_year: living_per_year[year] += 1 else: living_per_year[year] = 1 return living_per_yearThis code return the number of person in a population that are alive at the end of a year. You can use this doctest to test the code yourself if you want:

>>> count_living_per_year([(2000, 2003), (2001, 2002)]) == {2000: 1, 2001: 2, 2002: 1} TrueAs I said, this function described the algorithm at a very low level, doing everything. In the two nested for loops, it test if a year is in the dictionary, create the key and set the value at 1 if not, increment by one otherwise.

Great, but that’s a fake simplicity. The first downside I can mention is the risk of the writer.

We are humans

I am human, and I do mistakes. And other people too. So when you see a code like this, written by a beginner, there is a LOT of room for mistakes. And a lot of room for mistakes is worse than very little room for mistake, isn’t it?

Risk mitigation

Of course, risk of mistakes can be mitigated with automated testing, but if you want to rely on that only, you need to be sure of:

- Is the test for this feature already done? By who?

- 100% trust in the code coverage (Even 100% doesn’t guaranty that 100% of the code is actually covered, we’ll talk about that in the future),

- 100% branch coverage,

- 100% trust in the test correctness (Hard to reach, are you sure everyone who works on the test didn’t run the code, copy-paste the result as the expected output, without checking if it was correct?).

If you don’t, then you have to review the code, and spend some time/energy to make sure there is nothing wrong. And when you do, I guess that you prefer a code where risk of mistakes are low and where mistakes are easy to spot.

How to make simple things even simpler?

How to make something simple even simpler? Easy: don’t do it. If you don’t do something, it can’t be complicated, right? If you don’t do something, it “cannot not” works. Yes, not doing something yourself remove the risk of failing doing that thing right.

This sound stupid to you? Then read what follow carefully.

Step 1, remove the if statement

In the previous code, an

ifstatement was done to detect if a specific year was already in the dictionary:if year in living_per_year: living_per_year[year] += 1 else: living_per_year[year] = 1Let’s list what could go wrong here:

- Inverting the condition and the corresponding operation (invert line 2 with line 4), or write

if year not in living_per_yearinstead. - logical operator anti-pattern (

if not year in living_per_yearinstead ofif year not in living_per_year). - Typo in the augmented assignment e.g.

==, or in the value assigned if it’s a new year e.g.living_per_year[year] = 0.

So if you don’t code this

if, you can’t make those mistakes (and we all do mistakes, not matter our seniority, we can be tired, have a few seconds of inattention, etc…). But how to get rid of theifstatement? By using.get()to get a value, or a default one if the key is not in the dictionary:def count_living_per_year(population): living_per_year = {} for birth, death in population: for year in range(birth, death): living_per_year[year] = living_per_year.get(year, 0) + 1 return living_per_yearGreat! But… Hey, there is still a lot of room for errors here!

- What if you keep something close to the original code and use 1 as a default value? Whoops.

- What if you forget to change the augmented assignment (

+=) with the simple assignment (=)? Crash, Whoops again.

So…

Step 2, remove the dict.get() call

You want to keep the content of the for loop as simple as possible, to reduce risks. To do that, you can create a dictionary who will automatically create a default value if the required key is not already in the dictionary.

Did you ever heard about

collections? It’s a Standard Library Package, meaning it’s installed in Python that contains specials data-structures. Anddefaultdict? It’s a type of dictionary (in the packagecollections) that accept a default value factory (i.e. something that create a default value, e.g. a function, a class, or a primitive type likeintorlist) used when a key is missing.Let’s see how this can helps you:

def count_living_per_year(population): living_per_year = collections.defaultdict(int) for birth, death in population: for year in range(birth, death): living_per_year[year] += 1 return living_per_yearHey, it looks like the first version, but without the

if! Yes, it does. You add1for every year, leaving the rest to Python. Instead of implementing the key presence check yourself, you let Python do that for you. And trust me, it’s way more reliable than any human (not perfect, but “more” is already better!).Final step, let Python do… Everything

So, now, you have a function that count how many times a specific year appears in this double iteration and store the result in a dict, letting the check of the key presence in the dictionary to Python.

It’s not your responsibility anymore, you don’t have to write, test, read or maintain the code that does that, the Python team take care of that for you (consider sponsoring this team here!).

But… What do you do? You count how many times something appears and want a dictionary at the end? Hum… remember the

collectionspackage? Let’s see if there is something else useful inside.Hum,

collections.Counter, seems interesting, right? Take a few minutes to look at the documentation here.It is a collection where elements are stored as dictionary keys and their counts are stored as dictionary values.

That’s exactly what you are doing. So why are you doing it yourself instead of letting Python doing the job for you?

def count_living_per_year_(population: list[tuple[int, int]]) -> dict[int, int]: return collections.Counter( year for birth, death in population for year in range(birth, death) )“Wait, what is this thing, with the two for loops on two lines in a weird way?”

This is called a generator expression. To understand what it is, you need to know what is a generator. In a nutshell, in this case, it’s like a list comprehension, but it doesn’t create a list, just allows iteration over itself for one run (what

collections.Counterwill do). More information about that here.“Ok, so… What is a list comprehension?”

Here some reading for you here.

Now that you have learn many new things… Let’s run the test again:

>>> count_living_per_year([(2000, 2003), (2001, 2002)]) == {2000: 1, 2001: 2, 2002: 1} TrueGreat. It works. And is this new code more complex that the original one? Well, the two for loops is in a different place and might look weird if you aren’t used to list comprehension/generator expression syntax, but now, you do nothing except describing how to iterate over the population. Python is in charge of everything else.

We started here:

def count_living_per_year(population: list[tuple[int, int]]) -> dict[int, int]: living_per_year = {} for birth, death in population: for year in range(birth, death): if year in living_per_year: living_per_year[year] += 1 else: living_per_year[year] = 1 return living_per_yearAnd ended up here:

def count_living_per_year_(population: list[tuple[int, int]]) -> dict[int, int]: return collections.Counter( year for birth, death in population for year in range(birth, death) )Conclusion: Step by Step

This was an example of how you can delegate your work to Python and other tiers packages (more-itertools is an interesting one!) in order to reduce the usage of error-prone code, simplify the code, and focus on the task, not its implementation.

Yes, doing that require a great knowledge of Python and its ecosystem. But nothing prevent you to follow that path step-by-step. Start with simple things like

.get()methods, then when you get used to this tool, go one step further, etc.Keep in mind who will be asked to maintain the code too. Juniors? Seniors? Seasoned pythoneers? Try not to be too smart.

“Everyone knows that debugging is twice as hard as writing a program in the first place. So if you’re as clever as you can be when you write it, how will you ever debug it?”

Brian W. KernighanIf you can, teach and share your knowledge among your peers. If you can’t, try to set the required knowledge just above theirs. By doing so, your code will be easily understood after a quick documentation check, and the code base will thanks you.

Check out those recommended articles:

-

“Range len”, the anti-pattern

One step further on the way of Python: don’t count to get, just get.

A common anti-pattern used by Python beginners is the “range len” pattern. I’m pretty sure you already encountered this anti-pattern in the past, and there is even a high probability that you have done it yourself. I did too !

Anti-pattern

So let’s see an example of the anti-pattern:

for i in range(len(text)): print(text[i])Analysis

This seems pretty straightforward, but try to ask yourself, one line at a time: “What do we need? Why? How?”

1.

for i in range(len(text)): What do we need? We need the length of the text. Why? To get the upper limit of the range. How? By calling the length function and sending the result to the range function, then sent to the for loop to iterate over the range.Let’s move to next line.

2.

print(text[i]): What do we need? We need the text and the index. Why? To get the letter located at that index to print it. How? By using the index on the text string to get the value of the corresponding letter.Was our previous hypothesis true? No, the only read information that will get outside our block of code is the letter value. We needed the index to get to the letter value.

Anti-patterns are obvious, but wrong, solutions to recurring problems.

Budgen, D. (2003). Software designSo we don’t “need” the index. What we need is the letter. Was that obvious with the for loop code? No, we had to make assumptions, then read the implementation. And the implementation was in opposition to the for loop statement: We don’t need the index.

What to do?

So, the next question you need to ask yourself is the following one: “Can I get rid off the index as it’s just an intermediary value?”

If you can reduce the number of intermediary steps between the input and the output of a block, you will make the code more simple, less convoluted, faster to grasp, more meaningful.

How to do it?

In Python, for loops are designed in a way that it “only” asks the next value a data-structure can provide.

range(len(text))will provide all the indexes from0tolen(text)-1, one at a time, and the for loop will store that index into the variablei. But a string, a list, a dictionnary or any other iterable types can be used in for loops! The for loop will ask the next value at each iteration, and the iterable will provide it.This means that this code works:

for character in text: print(character)Analysis of the new pattern

Again: “What do we need? Why? How?”

Line 1

for character in text: What do we need? The text. Why? To get each character. How? By iterating over each letter with the for loop.Let’s move to next line.

Line 2

print(character): What do we need? The character. Why? To print it. How? Duh, with the print function!Yes, if this new code is not the first thing that comes in the mind of beginners, we have to admit that its explanation is quite… simple. Even more, you can almost read it in plain English, and it makes absolute sense: For each character in the text, print it.

-

“Hidden and”, the anti-pattern

One step further on the way of Python: don’t hide “and” with “if” nesting.

It’s very common to see nested “if” statements in code bases. And if the possibility to nest “if” statement make sense and can be very useful, there is a common anti-pattern easy to recognize and easy to fix. I call this anti-pattern the “hidden and” as it consist of hiding a logical “and” operator with a “if” nested inside another “if”.

Let’s see an example of the pattern and how to fix it:

![# Junior

if page > 3:

if len(book[page]["content"]) > 10:

print(book[page]["content"])

# Senior

if page > 3 and len(book[page]["content"]) > 10:

print(book[page]["content"])](https://i0.wp.com/thewayofpython.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/nested-if1.png?resize=967%2C387&ssl=1)

The anti-pattern and the fix The anti-pattern

This pattern is very common, so it’s important to be able to spot it quickly in code-review for example, to reduce the readability loss from the start.

Flowchart of the anti-pattern

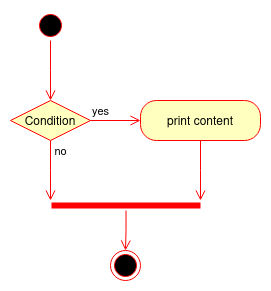

To understand the issue with this anti-pattern, I want you to take a look at the flowchart of the anti-pattern:

if page > 3: if len(book[page]["content"]) > 10: print(book[page]["content"])

Flowchart of the anti-pattern You can see that the first condition “no” and the second condition “no” point to the same merge point. In this case, this means that both conditions are de facto two part of a bigger one, the condition “first condition and second condition”.

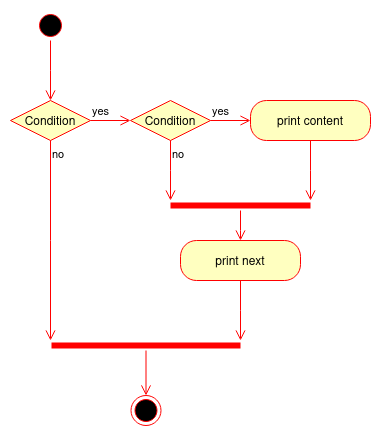

Flowchart of the “fix”

Now, let’s take a look at the flowchart of the following fix:

if page > 3 and len(book[page]["content"]) > 10: print(book[page]["content"])

Here, we don’t hide the “and” with a nested “if” statement and make the logical flow of the code more straightforward.

Don’t be zealous

If you think you recognized this pattern in a code base and want to explicitly show the “and” operator instead of using a nested if, you need to be careful and make sure you are in front of a “nested and”.

Have the look but isn’t a “nested and”

Sometimes, a nested if is what it is: a logic branch to do something in addition to the common path, where is logic merge after. Consider the following code:

if page > 3: if len(book[page]["content"]) > 10: print(book[page]["content"]) print("Next")You may have noticed and understood the difference. What’s after the nested if is what changes everything, because it’s a “common” part that needs to run without consideration to the nested if. We can see this flow merge in the following flowchart.

In this case, we are not in a hidden and operator case, because the first condition is part of the logic in itself.

Future merge not yet implemented

Sometimes, the anti-pattern appears but for a reason: the merge code isn’t yet implemented. If you are in a draft pull-request, for example, don’t fix it! Instead, ask the writer about the future merge and if there is any, suggest the addition of an ellipsis (“…”) to make the code more informative about the place of the future implementation:

if page > 3: if len(book[page]["content"]) > 10: print(book[page]["content"]) ... # a comment who shortly explain what's missing